Given everything that's happened to Uber in the last four months, it's instructive to go back and re-read the blog post that started it all, in which former Uber engineer Susan Fowler laid out abuses she claims to have experienced at the company. They include:

- A male manager who solicited her for sex on her very first day on his team and was not disciplined by HR because he was a "high performer" and it was his "first offense." Later, she claims to have discovered that the same manager had done similar things in the past.

- Having two formal performance reviews, which she claims were "perfect," downgraded after the fact by a different manager for unspecified reasons.

- Being part of a team where the managers bought custom leather jackets for all the men but not the women because they supposedly couldn't get a bulk discount on the women's coats.

All of these things are appalling, and some are possibly illegal. But maybe Fowler was an outlier, a particularly unfortunate employee who worked for a couple of particularly unprofessional managers. Or maybe she was lying or exaggerating.

That line of thinking quickly dissipated after a follow-up story in the New York Times three days later, in which reporter Mike Isaac collected similar stories of harassment and aggressive management behavior from more than 30 current and former employees.

Now, the results of the investigation by outside law firm Covington & Burling published on Tuesday make it crystal clear that Uber was running without some very basic management structures in place.

The investigation itself has not been made public, but the firm interviewed more than 200 people at the company and looked at over 3 million documents. Here are just a few of the 47 recommendations:

- Train human resources personnel to handle complaints -- from investigating possible harassment and discrimination to proper record-keeping.

- Mandatory training for managers, particularly if they're new.

- Consider a "zero-tolerance policy" for issues like discrimination and harassment, regardless of whether an employee is a "high performer."

- Prohibit any romantic relationship between "individuals in a reporting relationship."

- Prohibit the use of alcohol during work hours and make clear that the use of "non-prescription controlled substances" is not allowed at work or work events.

This isn't rocket science -- It's human resources 101.

And it's not just about making people feel good. Negligence exposes companies to employee lawsuits and fines from regulators. It also hurts recruiting and retention, which is vital in a hyper-competitive labor market.

So why did it take a blog post, numerous media reports of bad behavior, and a formal outside investigation to recommend basic HR practices? Where were board members like Benchmark's Bill Gurley, whose firm invested in 2011, or TPG's David Bonderman, whose firm invested in 2013?

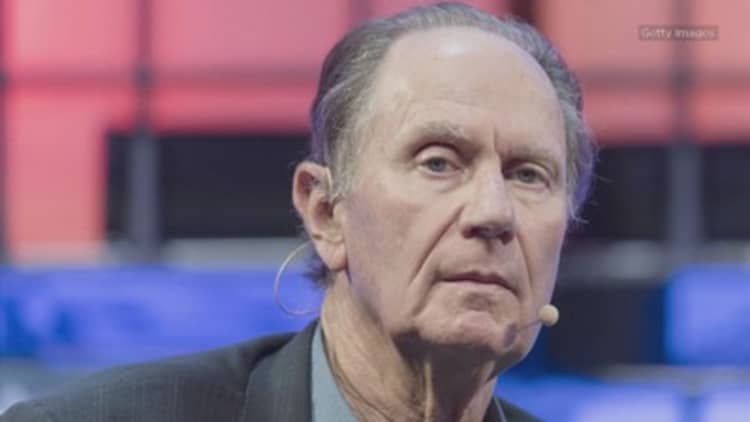

By letting things get this far, the board has become a big part of the story. Bonderman, in particular, resigned from the board after audio leaked of him on Tuesday making a sexist crack at Uber's all-hands meeting where the results of the investigation were presented.

Uber didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

Culture starts at the top. CEO Travis Kalanick, an aggressive and very skilled businessman, seems to have had a blind spot on some basics of management. He once sent an email to employees lamenting his need to be celibate at a company off-site because employees shouldn't have sex with anybody in their reporting chain.

Kalanick, like a lot of founders, surrounded himself with people who are similar to him in temperament and attitude -- a so-called "A-Team." Many of those people, like Emil Michael and Eric Alexander, have left or been fired in the wake of the current scandals.

Kalanick, meanwhile, is getting off relatively easy with a self-imposed leave of absence.

Silicon Valley worships founders. The conventional wisdom is that companies lose their spirit and competitive edge when they sideline founders and bring in adult supervision.

To some degree, this attitude is justified by results. Most of the runaway successes in tech, including Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Intel, HP, Oracle, and Microsoft, had their explosive growth phases under visionary founding CEOs.

There's also a growing body of evidence that founder-led companies outperform their peers because they instill employees with a sense of purpose and passion.

But there's another reason: venture capitalists are chasing the next Facebook or Google because that's how they make the big returns. If VCs gain a reputation for not being "founder friendly," they risk missing the next Mark Zuckerberg or Jeff Bezos or, indeed, the next Kalanick.

Wake-up call

Uber's meltdown suggests that VCs need to take a look at more counter-examples to the founder myth. There are plenty of highly valued start-ups with visionary CEOs who have stumbled. Parker Conrad at Zenefits was fired after allegedly encouraging employees to skirt the law. Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos faces at least one investor lawsuit and her company has lost the bulk of its value after it became clear that its core technology has never been proven to work.

There are also tech companies that became screaming successes with non-founders at the helm. Google brought in outsider CEO Eric Schmidt to run the company for 10 years with co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Cisco took off under John Chambers, who was not part of the founding team. Even Facebook, while run by Zuckerberg, brought in Sheryl Sandberg from Google to help steer the company through massive growth.

Every great founder succeeds as part of a team. Nobody does it alone. It's time for Silicon Valley investors to wake up to that fact and, when necessary, to save founders from themselves.